A family affair: Hinsons helped build Michigan’s infrastructure, Line 5

The men of the Hinson family in summer 1960 on the banks of Michigan's Tittabawasee River. Ralph Hinson (seated, at right), and his son Roy (seated, at left) helped to build the Line 5 crossing at the Straits of Mackinac. Roy's sons David (back row, left), Charlie (back row, right), Steve (in Roy's lap) and Mike (in Ralph's lap) are also pictured.

The men of the Hinson family in summer 1960 on the banks of Michigan's Tittabawasee River. Ralph Hinson (seated, at right), and his son Roy (seated, at left) helped to build the Line 5 crossing at the Straits of Mackinac. Roy's sons David (back row, left), Charlie (back row, right), Steve (in Roy's lap) and Mike (in Ralph's lap) are also pictured.

Son shares memories of his family’s work ethic, diligence

Sept. 22, 2021

Meet the Hinson family.

The family has a legacy of building big projects in Michigan—ones that protect the environment and heat homes and businesses.

The Hinsons’ story started after the Depression, in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula.

Halfway between Lake Superior and Lake Michigan lies the 95,238-acre Seney National Wildlife Refuge. It’s a preserve for migratory birds and other wildlife, including thousands of raptors, passerines and waterbirds.

Most nature enthusiasts embrace the area for its beauty.

For Michigan native Charlie Hinson, though, the area has extra special meaning: His grandfather, Ralph Hinson, helped revitalize it, following in the footsteps of such conservationists as John Muir.

In the mid-1930s, the elder Hinson worked for the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), restoring the area. A program under President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, the CCC resulted in the planting of more than three billion trees and helped shape the national park system the U.S. enjoys today.

As dragline operators who diligently guided large metal buckets and worked on construction projects across Michigan, Hinson’s grandfather Ralph and father, Roy Hinson, often would share stories about their work. As a child, Charlie Hinson relished hearing them, and one in particular spurred him to contact Enbridge recently via an email.

“My grandfather taught his heavy earth-moving skills to my father,” said Hinson. “So, the first place I lived (when I was born in 1953), was Indian River, just south of the Straits, where my family was working on Enbridge’s Line 5.”

The full appreciation of the contributions his grandfather and father made to Michigan’s infrastructure has come full circle, especially as he now reads about Gov. Gretchen Whitmer’s attempts to idle Line 5.

“Both my dad and grandpa were great sport fishermen, hunters and conservationists, who followed the rules,” said Hinson. “They always did.”

“They were experts at work and at play, and very proud of their work on Line 5. There is no way they would have done a haphazard job of laying pipe across the Straits. That pipeline is solid and built from the same strength of steel as the Mackinac Bridge. I know that, because that’s what my dad and grandpa always used to tell me.”

That partly is why he takes great umbrage to mischaracterizations of the durability of Line 5.

‘They built things to last’

“They built things to last,” said Hinson, “including Line 5. They were proud to be part of a new Michigan system designed and built to move the region forward.”

A married father of six, Hinson’s career entailed conducting surveys for cell towers.Although Hinson now lives in Kentucky, he has deep roots in Michigan, keeping up with Line 5 through his sister and two of his three brothers who remain in Michigan.

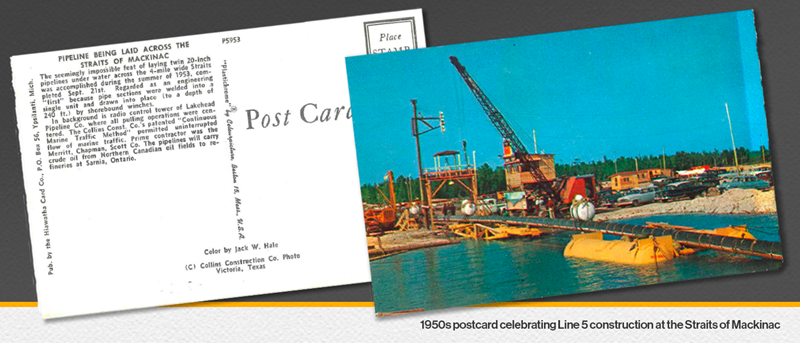

Line 5, which Enbridge placed into service Sept. 21, 1953, transports daily up to 540,000 gallons of light crude oil and natural gas liquids that help provide the propane, ethane and butane necessary for heating and the manufacturing of thousands of everyday products, including transportation fuel. More than half the State of Michigan relies on propane from Line 5, which includes meeting 65 percent of the Upper Peninsula’s propane needs.

Musing that he and Line 5 are approximately the same age, Hinson finds it unconscionable that the current administration is “ignoring the strong safety record of Line 5,” and trying to idle a well-functioning, vital piece of infrastructure on which Michigan, Indiana, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Wisconsin, and Ontario depend.

“Gov. Whitmer’s efforts to ‘get the oil out of the water’ paints a skewed representation of the facts,” said Hinson. “The fact is that Line 5 has proven to be safe and reliable over the last 67 years. That says a lot about the way it was built.”

Admittedly, Hinson said he listened intently to his family’s stories, though as a child, “didn’t give much thought” to how they might apply—until now.

Hinson, whose grandfather died in 1980 and dad in 2003, recalls how they often commented that construction of Line 5 was one of the best things for the region. He believes as committed environmentalists, skilled tradesmen and members of the International Union of Operating Engineers (IUOE), they would feel the same about Enbridge constructing the Great Lakes Tunnel.

Line 5 was ‘one of the greatest things we ever did’

“My dad and grandfather would have wanted to see the Great Lakes Tunnel go forward,” said Hinson.

“They thought Line 5 was one of the greatest things we ever did for the region. As long as we continue efforts to protect the Straits, they would want the Great Lakes Tunnel.”

Funded by Enbridge, the Great Lakes Tunnel will encase a replacement section of Line 5 deep below the lakebed. It will eliminate the chance of an anchor strike to Line 5 and essentially eliminate the chance of a spill from Line 5 into the Straits. Enbridge is investing $500 million to construct the Great Lakes Tunnel—another engineering marvel.